Artificial Artefacts

catalogue essay by Victoria Carruthers, 2021

In an attempt to define a body of work that defies categorisation, the surrealist painter Dorothea Tanning once stated that her seventy years of practice was driven by the desire “to capture the moment, to accept it with all its complex identities”; to draw in the viewer with known but unknowable states. I was reminded of these words the first time I saw the work of David Eastwood, with its similar oscillations between multiple states: real/imagined; ordered/chaotic; movement/stasis. The works in Artificial Artefacts display these same qualities continuing the artist’s fascination with the notion of the studio as a transformative space both in a literal sense but also as a metaphor for the imagination.

Perhaps this is most evident in the two large paintings that are pervaded by a surrealist combination of consummate naturalism and a dreamscape in which something otherworldly is unfolding. In Penumbra (2020), Eastwood creates a copy of his own studio by digitally modelling the space in 3D and emptying it so that only the staircase, the checkerboard floor and two power sockets remain. Thus, he transforms the studio, his own studio, into a familiar yet strangely depersonalised space, opening up the possibility for the viewer to enter. Penumbra and its ‘pair’ Outlier (2021) recall the dramatic use of light and shadow in Baroque interiors. Eastwood references the eerily still interiors of Vermeer by appropriating the checkerboard floor to invoke the grid of order and perspective initiated by Alberti in the Renaissance. In The Art of Painting (1666-68), Vermeer questions the nature of reality through a commonly used conceit of the period: depicting himself painting a subject in his own studio. In the foreground a curtain has been pulled back to reveal the scene into which the viewer is invited. This is, of course, another framing device, the voluptuous folds of drapery so evocative of sensuality in the Baroque style are rendered in the sumptuous texture of the fabric that floats above the floor in both of Eastwood’s large paintings. A common motif for transformation, cloth here conceals a rupture in the studio space: underneath it something is taking place. In Outlier, a disembodied hand emerges from under the fabric, made all the more enigmatic against the deep chiaroscuro of the background. In Penumbra, a pale foot protrudes from the shape trapped in the fabric: but it isn’t human. In fact, rather than being disembodied, it emerges mounted on a block, a ready-made artefact of the studio, a nod in the direction of ‘life’ drawing, yet very clearly not alive. It is the first of many objects in this collection caught in a recursive action between artist and artwork, questioning the nature of perception, reality and representation.

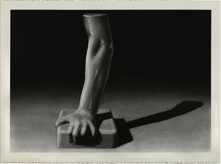

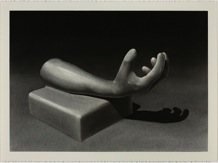

The motif of dismemberment is explored most unsettlingly in Eastwood’s series of six charcoal drawings. Each work features a body part designed to look artificial, invoking the idea of a studio model, again for life drawing. However, the notion of any functionality is radically undermined by the complexity of the technical process and the formal aspects of the composition. The body parts are made from 3D scans of Eastwood’s own anatomy. According to the artist they are “transformed into a series of virtual objects” simulating “studio artefacts of a type traditionally found in artists’ ateliers”. Yet these fragmented parts evoke more than the polished skulls and anatomical plaster casts of antiquity. They are also reminiscent of death masks, gothic disturbance, medical prosthesis, the fetish of the uncanny – they are ghostly replicas, simulacra. What at first appear to be clinical white surfaces, porcelain-like approximations of the real, also contain the hint of fleshiness, evident in Prop (2021) with the press of metal against the supple tissue of a forearm. In Mask (2021) and Limb (2021), the sheen on the surfaces makes the objects appear at once viscous, sticky, smooth and satiny. The fingers in Hold (2021) seem to have a plasticity about them, as if they were stopped in time whilst offering us some invisible object. In contrast to the Renaissance bust, which implies a continuity with a unified and idealised body, these objects remain defiantly fragmented. Eastwood has created a representation of himself, of the artist’s hand, as an indexical artefact, appearing on the paper through layers of organic charcoal. There is a poetic recursiveness in the transformative potential of these works and in Eastwood’s beautiful painterly work. Like Vermeer, he creates his own conceit, his own sleight of hand, to draw together the artist, the viewer, and the act of painting. The universe of the studio is revealed in these works as a liminal space in which the artist’s alchemies collapse the boundaries between the real and the imaginary, the past and the present, to capture the moment in all its complex identities.

© Victoria Caruthers. Originally published in David Eastwood: Artificial Artefacts, exhibition catalogue, 2021.

Decoy Décor

catalogue essay by Ian Grant, August 2011

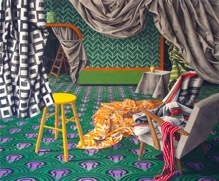

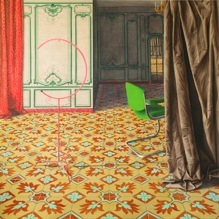

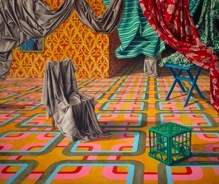

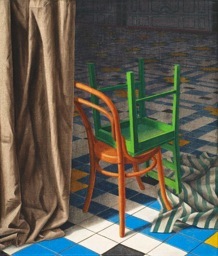

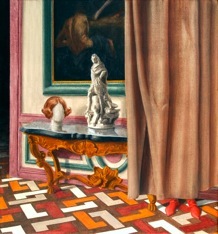

David Eastwood’s paintings offer us intriguing and constructed realities that have had no prior existence. They are a gathering together of elements, taken from many sources, selected and deployed for their part in these fabrications. The paintings are worked from neither a directly photographed nor a directly observed single reality. Eastwood slightly manipulates perspective, evokes associations between various elements, hinting, perhaps teasing us, at historical and contemporary sourcing as he builds this reality with confidence and virtuosity. The paint is evenly applied and there is no backing away from sharp focus and certainty of representation. The components in the paintings are formed from precise analytical observation and assembled with equally precise compositional understanding. To do this one must draw on not just skill, but an intelligence sometimes underrated by those who have little experience with the demands of what he seeks to do.

There is also our sense of recognition of both the total image and all of its components to be considered. We are offered hints of Dutch interiors in the patterned floors, or is it hints of Leagues Club carpets? We can find imagery we may link to De Chirico, to Magritte, to late medieval painting or even to a contemporary furniture catalogue – or perhaps not. We need make no conclusions, our response to the paintings doesn’t hinge on the certainty of our deconstruction. We can just explore them, admire them, and allow for possibilities in our imaginations, knowing that there are no correct conclusions that we must arrive at. They evoke stories but they don’t tell us stories, and this is what we enjoy in them.

There is evidence of activity and objects that might relate to humans, but no figures to become the centre of both image and interpretation. Eastwood is very familiar with Dutch interiors of the Vermeer kind but he chooses to not employ ‘staffage’ in his imaging. The hinting of human presence is enough and the completion of any narrative remains the prerogative of the spectator.

We are given carefully considered titles for his works and again, very much in the contemporary manner, these titles remain evocative but open. The works are clear, the selection and imaging of all their parts is precise, the composition is carefully considered and the suggestion of possible meanings is deliberate. Yet a precise meaning, if it is needed, remains tantalisingly unspecific and must reside for each spectator within their own response. This is Eastwood’s intention and very much an integral part of these remarkable and absorbing paintings.

© Ian Grant. Originally published in David Eastwood: Decoy Décor, exhibition catalogue, 2011.

Draped, folded and concealed

by Prue Gibson, 2010

[Excerpts from the original essay only.]

Artist David Eastwood creates theatrical interior scenes, unreal and manufactured, where imaginary possibilities are played out and where emptiness can be a conjuror’s trick.

...Eastwood has spoken about the “presence and absence” in his work — the potency of the empty space. The idea of the ‘near and far’ is also at work. Far back, the space seems to continue for ever, into the darkness — and darkness is associated with our mortal fears... While the artist eschews the idea of purposeful malevolence in his paintings, fear is nevertheless there, as it always is in life.

© Australian Art Review and Prue Gibson. Full essay originally published in Australian Art Review, Issue 23, May - July 2010, pp62–63.

Profile / David Eastwood

by Joe Frost, 2009

In his paintings David Eastwood plays with the forms of the world like pieces in a game. It’s a game that’s easy for us to enter, for the interior spaces he represents are dense with things we recognise: patterns that bring immediate associations, and familiar objects.

The paintings make a dazzling first impression, but in time they deepen and become strange. The stool in the near distance of one painting seems oddly scaled for what sits around it, and the background in another picture opens onto discontinuous spaces at left and right. One ambiguity after another complicates what had seemed at first to be a stable image, and it becomes clear that although these paintings refer to the world we live in, their relation to it is tangential and mysterious.

There are seldom windows in his interiors, and of all the patterns, forms and objects they contain, one source he never draws upon is the natural world. When asked about this he considers it thoughtfully. “From time to time I’ve thought of including flowers. It’s a short step from having a vase to having flowers. But I thought the empty vase was consistent with the empty room.”

It makes sense that an artist whose depicted world is wholly invented excludes nature. Painting is not, for him, an occasion to observe the things that preceded human culture but to claim his status as a creator in his own right.

But working in the studio Eastwood finds his way to a raft of references beyond the studio door, and his paintings’ content is rich. They are about the ongoing invention of art, specifically the art of the western world. Their bricolage of inconsistent historical styles suggests that we are the product of what has come before us, a weighty idea that he bears lightly and happily, judging by his diverse borrowings.

The paintings also possess a personal dimension of humour and pathos, expressed through the treatment of inanimate objects as almost-human agents. “An empty chair is both an absence and a presence”, he explains. “I’ve often used techniques to make the chair less about an absence by maybe draping it, and making it like a draped figure, or placing something on the chair, something to make the chair active in the picture.”

Although he has occasionally painted a figure into a composition, he prefers to imply the human presence using props, which stand for the idea of people’s relationships. The allusions he makes in this way are not vague. His paintings have depicted couplings, estrangements, stand-offs and solitude, all couched in terms of wood and cloth, plastic and metal.

Eastwood is an admirer of Dutch painting of the seventeenth century, and he enthuses that “in the work of many of these painters there is playfulness, sometimes even a bawdy sense of humour. The painter is giving the viewer a nod and a wink.”

On a trip to Europe earlier this year, where he was Artist-in-Residence at the Australia Council’s Paris Studio, Eastwood searched out some remarkable decors and was able to look again at the museums. He gave special attention to the work of the Flemish painters, Van Eyck, Van der Weyden and the Master of Flémalle, for the oddness of their pictorial structures.

“Without the overriding system of single-point linear perspective to create a consistent, wholistic space, there’s a distorted quality in their work, as though the whole scene is inside a warped, squashed box. Being pre-High Renaissance, it’s a little less ‘all figured out’.”

He also made two special journeys to see exhibitions by the Leipzig-based painter Matthias Weischer, whose work bears a strong relationship to Eastwood’s. Although Weischer’s interiors appear dilapidated and are painted more scruffily, they are similarly pieced together from fragments that only just hold together.

It is interesting that he should seek out an artist whose work has had such dark undertones because for all the invention, historical awareness and even fun that characterises Eastwood’s paintings, there is darkness in them, literally and figuratively. They convey an uncanny feeling of emptiness, as though an event of some import is about to happen, or has perhaps already occurred. Is he alluding to some sort of pain, a personal loss or a more general sense of dread that is collectively ours?

“That’s a good question. And difficult to talk about because it’s not something I try to direct. The sense of atmosphere and mood is something that I enjoy about the work, but in some respects it’s surprised me a little bit. They’re imagined places, and so there’s a strangeness in the work that I don’t really understand but I feel like I’m mining something in myself. So in that respect I consider them psychological interiors. What comes out in the painting is something hitherto unknown.”

That his paintings strike such an ambiguous chord is a testament to how Eastwood has developed in his first decade as a painter, for in his earliest years he worked quite differently. Painting was a slow labour because he worked with a small brush, modelling in opaque colour through several layers, with fewer creative decisions to make along the way. His paintings were vivid, but for all their nimble intelligence their surfaces were utterly controlled.

Later he began making drawings, finished works in charcoal and graphite. The absence of colour and the warm grain of the paper transformed the imagery. While his paintings had been extroverted the drawings were contemplative, and when Eastwood started to paint on craftwood instead of canvas he found a similar touch in paint. In the ‘bookmark’ series, small paintings of notes and paper scraps found in library books, he achieved an effect in painting similar to the drawings.

Now he works freely on large canvases, painting one form then another in thin acrylic paint without knowing the final composition. He explains: “I enjoy starting a painting not knowing how it will end up. I might start with something in the foreground to frame the space and slowly work towards the background, adding things as I go. This approach suits me better than making detailed studies because I feel more energised during the process, to see how something will turn out. Even though there might seem to be a lot of control in the sort of images I make, there is always an element of chance and surprise in the way I construct the paintings of interiors.”

Is art something to be dictated or does it work its will through the artist? Eastwood’s practice of painting has delivered him to content deeper and more ambiguous than he’d consciously sought, content that lives in the traditional forms of painting. But the freedom to play with those forms has come through sustained effort; at every stage of his development he has thought afresh about his intentions and approach.

His paintings allow us to experience for a moment, a consciousness that exists outside of time but contains all of time. The pleasure of looking at them is a form of ecstasy in the sense implied by the word’s Greek origin: standing outside oneself, free of ordinary limitations and restrictions. Yet he returns us to the world we know, and his paintings contain an awareness that, although disguised, is unmistakeable as the situation of being human.

© Artist Profile and Joe Frost. Originally published in Artist Profile, issue 08, 2009, pp66–69.

Mise en scène

catalogue essay by Gary Carsley, October 2007

One of the more interesting ironies about modernity, specifically in respect to visual art, is that often one of the most accurate indices of a work’s contemporaneity is the degree to which it successfully rearticulates positions and techniques originating in the past. Before the western tradition developed a schema for the naturalistic rendering of objects within space, the elements making up a painting’s narrative – a diadem or a tabletop for example, were depicted singularly as was the area surrounding them. On the basis of the similarities between this process and the way in which Photoshop and other digital imaging programs work by allowing for the isolation from the overall picture space of an object and its immediate environment it is possible to argue that the recent work of David Eastwood has aspects that are both inside and outside their time.

The works of which I write have a strong sense of pattern and heightened optical effect evidencing as much a debt to Bridget Riley as they do to the fabrics and wallpapers of the 1970s. These paintings are characterised by a light source that is generally consistent across their surface working to naturalize and coagulate the disparate elements – a plastic IKEA chair, wallpaper derived from Vermeer or the carpet from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining within the apertureless and theatricalised space that is quite possibly more stage than canvas. In these works David Eastwood is as much director as painter. The furniture with its eerie sentience has a disquieting aspect that is best understood by reference to the term character actor. As do other various objects, which, like everything else in this series of paintings, are meticulously rendered in a halo of fictive space that Eastwood uses to quarantine his actors.

It is the discourse between these hitherto mute objects that links these paintings with current Mise en scène strategies. For Eastwood the pictorial space of the canvas has become a theatre set, a site of action, a rhetorical space where a sort of static, ritualised drama is staged. In these new works a formal and conceptual approach is emerging that has affinities with the theory and practice of cinema and the theatre. It is a new direction for Eastwood. The artist as director interestingly enough has its origins, as does single point perspective, in the early renaissance, when artists elaborated pageants and other forms of spectacle that were - as are the recent works of David Eastwood - complexly coded, often oblique, associative narratives.

© Gary Carsley. Originally published in David Eastwood: Mise en scène, exhibition catalogue, 2007.

The Meeting Place, 2006

Where Your Eyes Don’t Go, 2006-07

Green Room, 2007

Gold Room, 2008

This Bird Has Flown, 2009

Holding Pattern, 2009

Obstacle, 2010

Anonymous 4, 2004

Catalogue, 2006

Wait, 2009

Incognito, 2010

Prop, 2011

Nightwatch, 2010

Limb, 2021

Prop, 2021

Outlier, 2021

Penumbra, 2020

Limb, 2021